“Essentially, it allows you to be green by saving green—and by that I mean money,” says AJ Glassman, 15, of GreenMyParents, an environmental movement making its way through social networking sites and dinner table discussions across the country.

Launched on Earth Day 2010, founded by Tom Feegel, and championed by teenage environmental savant Jordan Howard, GreenMyParents (GMP) adds a layer of economic incentive to simple eco-friendly tasks kids can do around the house, allowing families to save money and the environment in one fell swoop.

There are only four basic steps.

In step one, a child identifies an area in her home she feels can be greened. A starter kit on the GMP site identifies “energy vampires.” If left plugged in, energy vampires like fax machines or DVD players can waste up to 10 percent of an average family’s monthly electricity bill. Per family, that’s $100 a year. Extrapolated nationwide, the amount is a head-scratching $10 billion.

Having identified her target area, the parent-greening child proceeds to step two: pitching her parents on the merits of eliminating their home’s energy vampires. If her parents agree, a contract is signed, whereby the parent greener would earn a percentage of the money saved.

Motivated by her success—the extra change in her piggy bank—and the feeling of doing grown-up stuff, she takes step three: broadening her green endeavors to other areas in the home.

Feegel is quick to cite a food example. “If a family switched three pounds of meat for three pounds of vegetables one day a week, they would save $750 a year.”

Lastly, in step four she uses the limitless possibilities of social networking to advocate on the movement’s behalf: A post on GMP’s Facebook page. A tweet about how much money she saved her folks.

A Bumper Sticker Birth

A few years ago, Feegel, who is also the CEO of Brand Neutral, an environmental consulting firm, was searching for a way to unite the “different slivers of the environment’s micro-movements.”

Be it through his business dealings or his personal charitable donations, he had been in direct contact with many environmental nonprofit organizations.

“There are organizations that do such great work and they have to be funded and they have to acquire new members—but that isn’t what they are in the business to do,” says Feegel. “Fundamentally, it raised a difference of opinion for me of about how we should all be keeping score.”

This need for a new calculus, plus a recurring theme Feegel observed when he was chief of staff to former Vice President Al Gore’s 2007 Global Concert event—that many adults said they were only going green “for their kids”—were percolating in the back of his mind in 2008 when he and his young son stopped at a red light in the family car.

“There was a bumper sticker on the car in front of us that read ‘Proud Parent of an Honor Student’,” says Feegel. “And my son asks me, ‘What if kids put stickers on their parents’ cars that said ‘I’m proud of my parent’?’”

Meeting Jordan Howard

This is how he met Jordan Howard, 18, the green advocate extraordinaire who “changed GMP forever,” says Feegel.

It was Howard—of Girls Gone Green and Rise Above Plastics—who came up with the idea to intertwine Feegel’s nascent concept with economics.

“Who doesn’t want to save money? Who doesn’t want to put money in their pockets?” says Howard.

Howard doesn’t just preach; she practices, and has pitched GMP to more than 200 children since April.

“I came up with the idea of creating this garden and trying to grow most of the things we eat in our home,” says Howard, whose parents bought into the notion of GMP almost immediately.

She estimates that the backyard garden, which produces onions, Swiss chard, zucchini, and paprika, has saved her family of six roughly $40 per month over the past year.

Howard says she declined to accept the money owed her as a result of the contract she signed with her parents, choosing instead to create a “family fund” to be used for something big, “like a vacation.”

GMP’s accounting is on the honor system, similar to how a Boy Scout says he learned to tie a knot and then earns a badge. “Kids get enough report cards, we’re not going to audit them,” laughs Feegel. “A parent-endorsed pledge of a specific number is plenty.”

Eventually, Sanchez persuaded his parents that the family’s addiction to two cases of bottled water per month had to go. Now, the Sanchezes use filters and re-usable canteens.

Eventually, Sanchez persuaded his parents that the family’s addiction to two cases of bottled water per month had to go. Now, the Sanchezes use filters and re-usable canteens.

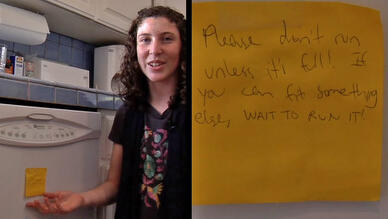

Clara has placed environmental reminder sticky notes on the door of this refrigerator—and roughly 15 other spots around the family home.

Clara has placed environmental reminder sticky notes on the door of this refrigerator—and roughly 15 other spots around the family home.